9 Guide to the Release Conditions Matrix

After reading this guide, team leads will understand the benefits of using a Release Conditions Matrix and how it can assist judicial officers in deciding a person’s pretrial release conditions. Team leads will be able to help their jurisdiction’s policy team create its own matrix.

Introduction

The Release Conditions Matrix is an instrument that local policymakers develop to help match pretrial release conditions with a person’s scores on the PSA. Every jurisdiction that uses the PSA should create and use a Release Conditions Matrix. The PSA is used to assess the likelihood of pretrial success or failure and the Release Conditions Matrix can help people appear in court and remain law-abiding. On its own the PSA does not direct a judicial officer to release or detain a person or recommend any specific release conditions. The PSA results may help inform the decisions a judicial officer makes. The matrix is designed to help judicial officers use PSA scores to make decisions that are based on the assessed likelihood of pretrial success or failure, are consistent with the risk principle, [1] align with statutes and local policies, and take into account available resources.

To create the Release Conditions Matrix, it’s best if every member of the policy team has basic knowledge about the legal foundations of pretrial justice and empirical research on what works to help people appear in court and remain arrest-free. It’s also useful for your team members to be familiar with empirical research on actuarial pretrial assessment and pretrial release and detention; national pretrial standards for best practices; and your state’s pretrial laws and rules. When a team is knowledgeable about these topics, the process of creating the matrix proceeds more efficiently and the end result may better achieve your jurisdiction’s pretrial goals.

Many jurisdictions find it useful to consult with national pretrial experts to educate the policy team and other stakeholders about the topics listed above and to assist team members in creating the Release Conditions Matrix.

Let APPR know. We’ll be sure you receive notice of the latest on the PSA—like scoring rule updates—and free trainings on pretrial best practices.

The PSA newsletter is designed to keep users and stakeholders up to date on the tool, highlight innovations in the field, and help pretrial systems assess pretrial risk fairly and consistently.

The Center for Effective Public Policy, which implements the APPR initiative, is available to provide tailored support to jurisdictions implementing the PSA.

The Release Conditions Matrix

The Release Conditions Matrix has two sections:

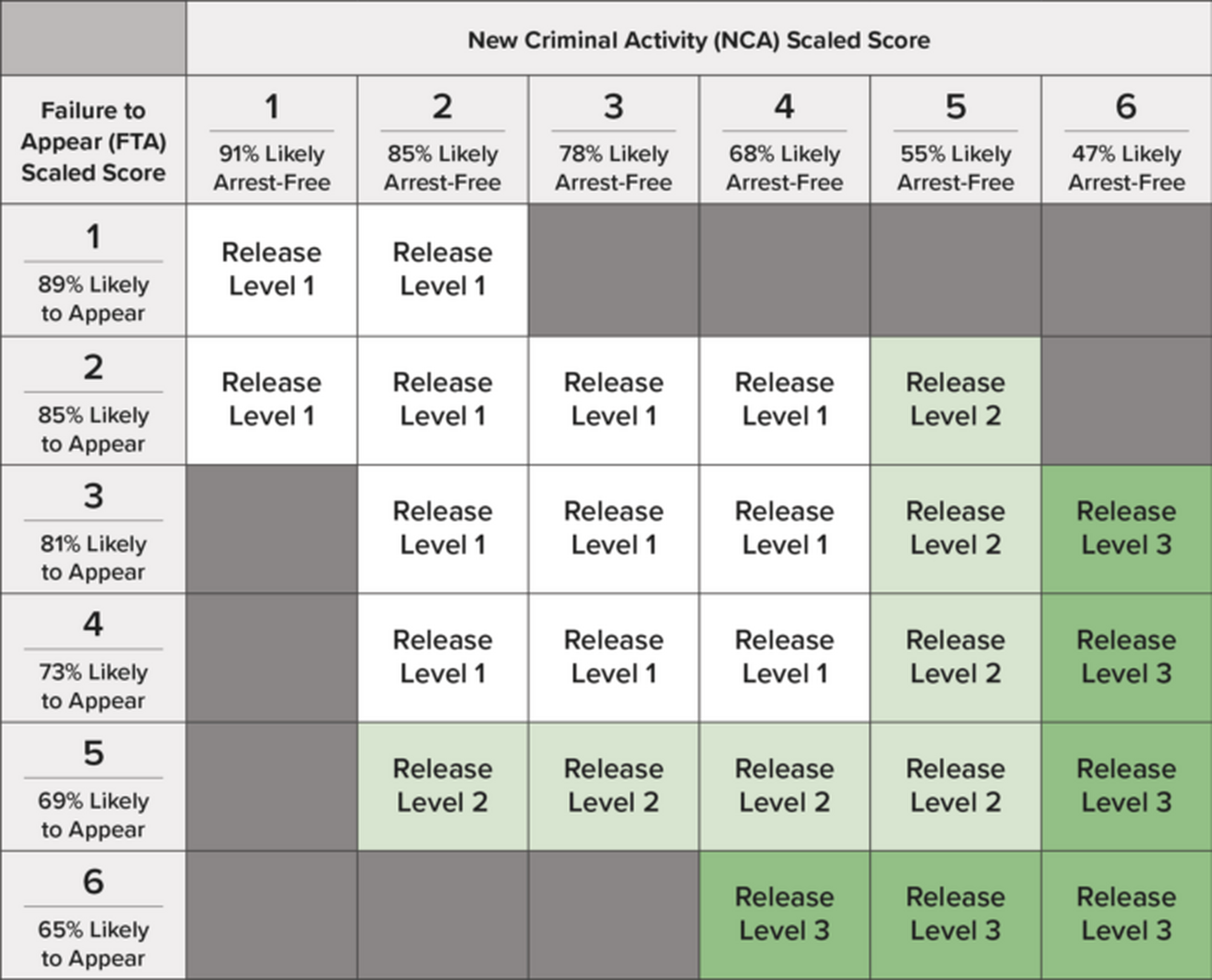

- a grid, which is a structured tool that matches a person’s scores on the two PSA scales (FTA and

NCA) to presumptive levels of pretrial release; and - a table that lists the conditions associated with each pretrial release level.

Some jurisdictions also include a third section that provides additional information, such as the seriousness or type of charge and/or unique circumstances about a case. A Release Conditions Matrix guides judicial officers on how to match conditions of release to people who have a range of PSA scores. Detention is not included in the matrix because eligibility for detention is based on federal and state law, and the matrix becomes relevant only after a judicial officer decides a person will be released.

This is an example of a Release Conditions Matrix. (See Examples of a Release Conditions Matrix for more samples and a blank matrix for your team to complete.)

Example of a Release Conditions Matrix

Note: The first section of the matrix is a grid, a structured tool that matches a person’s scores on the two PSA scales (FTA and NCA) to presumptive levels of pretrial release. Here is one example:

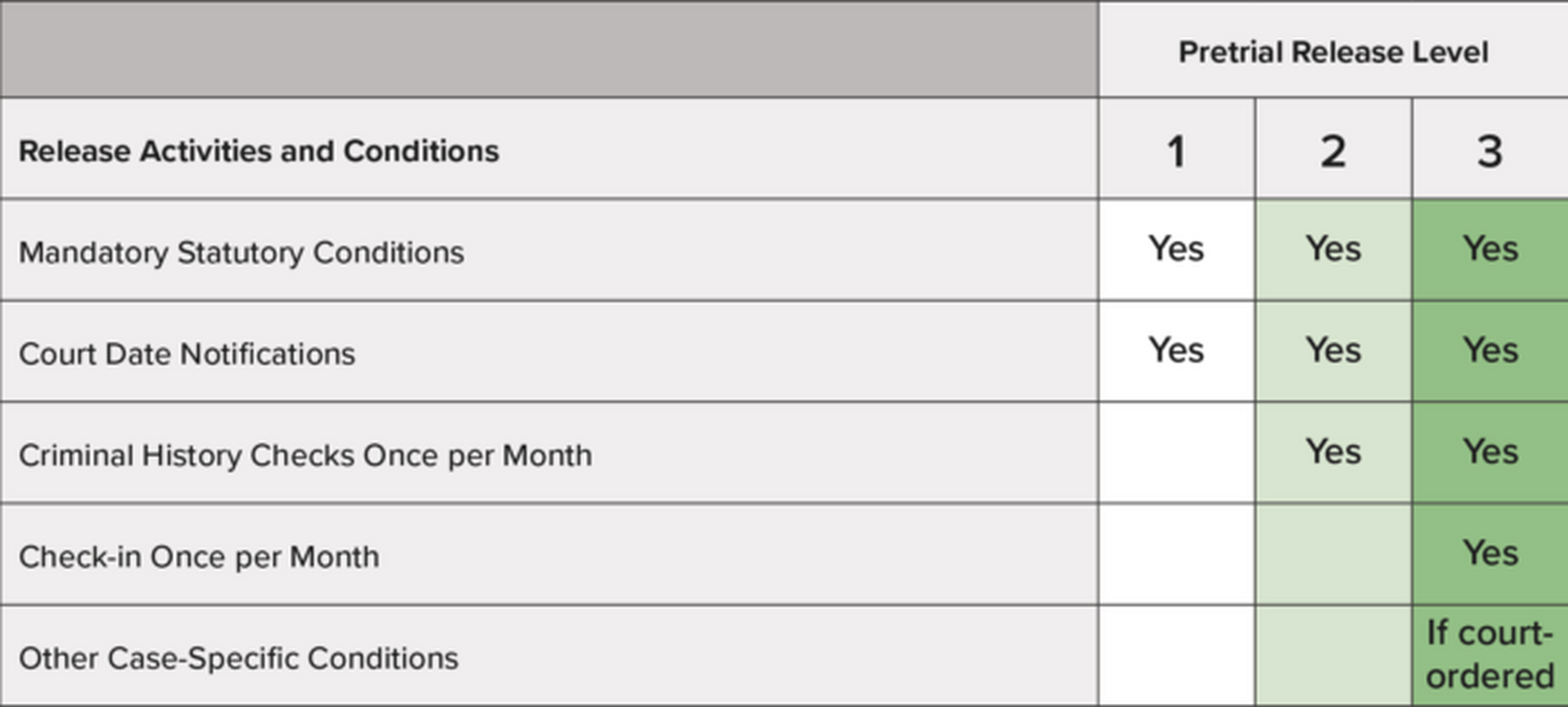

Note: The second part of the matrix is a table detailing the conditions associated with each level of pretrial release. Here is one example:

Mandatory Statutory Conditions: The person appears in court for all hearings (and abides by all laws if statutorily applicable).

Court Date Notifications: The person receives all court date notifications and replies if requested.

Criminal History Checks: The person’s criminal history is checked for new criminal charges at least once a month.

Check-ins: The person checks in with a pretrial staff member at least once a month. At the staff member’s discretion, check-ins may occur in person or by telephone or videoconference.

Other Case-Specific Conditions: (such as No Contact Orders, Substance Testing, or Electronic Monitoring): If one condition or more is court-ordered, the person complies and the pretrial staff member monitors the person’s compliance.

The structure of the Release Conditions Matrix is based on the following legal principles and evidence-based practices:

- People should be released with the least-restrictive conditions necessary to provide the judicial officer reasonable assurance that they will appear at future court hearings and, if legally relevant in your state, will not endanger community safety during pretrial release. [2]

- The presumptive pretrial release level should be commensurate with a person’s assessed likelihood of pretrial success.

- People assessed as having a higher likelihood of pretrial success should typically be released with minimal or no conditions. [3]

- People assessed as having a lower likelihood of pretrial success should be released with conditions targeted to help them appear in court and remain law-abiding. [4]

As the sample matrices illustrate in Examples of a Release Conditions Matrix, if a person receives relatively lower scores on the two PSA scales, little if any monitoring should typically be imposed. When a person receives relatively higher scores on the two PSA scales, the nature and intensity of pretrial monitoring typically increases, provided that your jurisdiction has the monitoring resources available.

The levels of release may include different types of reporting (such as by phone or in person), different frequencies of reporting (for example, weekly or monthly), and special conditions (such as electronic monitoring, curfews, or no-contact orders).

Research suggests that the use of a Release Conditions Matrix will result in more consistent and proportionate decision-making. In fact, one study demonstrated that judicial officers usually make decisions consistent with a pretrial matrix’s guidelines and that people in jurisdictions where a matrix was used appeared at their court dates at higher rates and had higher rates of law-abiding behavior than those in jurisdictions where a matrix was not used. [5]

The grid reflects a person’s two PSA scores. Many jurisdictions also want their Release Conditions Matrix to include additional information, such as the seriousness or type of charge and/or unique circumstances about a case. For instance, a person charged with a first-degree violent offense who has no criminal history will score very low on the PSA. Without any additional guidance beyond PSA scores, the matrix would place the person on a low pretrial release level, possibly resulting in few if any conditions. Given that, many jurisdictions make a policy decision to include additional guidance, for example, that the judicial officer consider placing someone charged with certain serious violent offenses at a higher release level—or the highest—regardless of the person’s PSA scores.

The next section describes the steps your policy team should take to complete a Release Conditions Matrix for your jurisdiction.

Creating a Release Conditions Matrix

A subcommittee or the entire policy team can do the work needed to create a Release Conditions Matrix. If a subcommittee is responsible for these tasks, its members should present the matrix to the full team for approval. Critical participants are representatives from the criminal justice agencies that have a role in pretrial decision-making, perform day-to-day pretrial practices, and/or are affected by pretrial policies and practices. These representatives usually include judicial officers, prosecutors, defense attorneys, pretrial services staff, detention staff, court administrators, law enforcement officers, and victim services staff.

The team members who create the Release Conditions Matrix should have a basic understanding of pretrial law, empirical research, and the pretrial resources and services that are or will be available to people in your jurisdiction who are released. You may want to create an inventory of those pretrial resources and services and make it available to the team during the meeting when you discuss the matrix.

At the subcommittee or policy team meeting—or beforehand—the team lead should provide members with a copy of this guide as well as the Examples of a Release Conditions Matrix. Some jurisdictions find it useful to convene a few members prior to the meeting and use these examples to prepare a first draft of the matrix. This provides an early opportunity to take stock of your jurisdiction’s available pretrial resources and how they could be allocated for people who are released.

It may also be useful for meeting participants to review and gain a shared understanding of the Release Conditions Matrix and its purpose. PowerPoint slides are available for this purpose (see the Release Conditions Matrix Presentation at advancingpretrial.org/guides).

The team should decide the following during the meeting:

- how to customize the matrix, including its layout and the pretrial release level to specify in each box of the grid;

- which conditions will be associated with each pretrial release level; and

- whether any additional information related to unique circumstances is wanted.

These tasks are discussed in the following sections.

Customizing the Grid

The Examples of a Release Conditions Matrix, which include a blank matrix, are the first things the subcommittee or team should consider. As a team, you should decide everything about the grid’s presentation—from the colors used to shade each box to the level of release specified in each box. You can adjust the names of the pretrial release levels to conform to what already exists in your jurisdiction. For example, Release Level 1 is intended to be the equivalent of being released on one’s own recognizance (commonly abbreviated as ROR or OR) with no additional conditions.

The Examples of a Release Conditions Matrix, which include a blank matrix, are the first things the subcommittee or team should consider. As a team, you should decide everything about the grid’s presentation—from the colors used to shade each box to the level of release specified in each box. You can adjust the names of the pretrial release levels to conform to what already exists in your jurisdiction. For example, Release Level 1 is intended to be the equivalent of being released on one’s own recognizance (commonly abbreviated as ROR or OR) with no additional conditions.

When creating the grid, team members should keep in mind the legal principles and evidence-based practices that the Release Conditions Matrix is based on. They are repeated here as a reference, and a PowerPoint slide in the presentation materials lists them.

- People should be released with the least-restrictive conditions necessary to provide the judicial officer reasonable assurance that they will appear at future court hearings and, if legally relevant in your state, will not endanger community safety during pretrial release.

- The presumptive pretrial release level should be commensurate with a person’s assessed likelihood of pretrial success.

- People assessed as having a higher likelihood of pretrial success should typically be released with minimal or no conditions.

- People assessed as having a lower likelihood of pretrial success should be released with conditions targeted to help them appear in court and remain law-abiding.

The subcommittee or team should develop the grid with a typical person in mind. That is, the pretrial release level selected for each box should be what the jurisdiction’s stakeholders typically want for people who receive those scores on the two PSA scales. These become the presumed conditions. In cases when there is some reason to deviate from the presumed conditions, such as the presence of certain violent charges, the team can include additional guidance to help judicial officers decide how they might respond.

When jurisdictions first implement the PSA, they will not know their local pretrial success or failure rates associated with the PSA scaled scores. Each jurisdiction can expect to see lower pretrial success rates among the people who have higher FTA and NCA scaled scores. But the particular success rates for scores in any given jurisdiction will not be known until the PSA is used locally and data are analyzed.

For example, in the jurisdictions in which the PSA was developed and validated, a scaled score of 1 on each of the FTA and NCA scales was associated with an average likelihood of approximately 90 percent success. But in any jurisdiction implementing the PSA, the success rate corresponding to a score of 1 is initially unknown. This unknown rate makes it challenging for the policy team to decide how resources should be allocated for people who are released. The same challenge exists for scores 2 through 6.

For purposes of constructing the jurisdiction’s initial matrix, the policy team may want to consider the results (success and failure rates) associated with the jurisdictions involved in the PSA’s development and validation. That information is provided in PowerPoint slides for your reference (see PSA Results Presentation). The templates provided in the Examples of a Release Conditions Matrix include the results from the PSA’s development and validation studies.

Whatever approach the policy team takes, the group should commit to analyzing the jurisdiction’s success and failure rates after PSA implementation and adjusting the matrix as needed (such as increasing and/or decreasing monitoring and resources for people at different pretrial release levels). Over time and with ongoing analysis, your jurisdiction’s allocation of resources will likely become less subjective, more data-guided, and more efficient.

Customizing the Pretrial Release Level Table

The Release Conditions Matrix should include a Pretrial Release Level table that specifies the conditions associated with each level. The Examples of a Release Conditions Matrix presents a few such tables. The team or a subcommittee should create its own Pretrial Release Level table (which may include more rows or fewer) and some content that may be different from the examples. Your table should be based on local pretrial practices, the pretrial resources available in your jurisdiction, how those resources will be allocated for people with varying PSA scores, pretrial legal principles, and evidence-based practices. Again, note that “Release Level 1” in the examples is the lowest level of release and is the equivalent of being released with no additional conditions (known in most jurisdictions as being released on one’s own recognizance: ROR or OR).

If pretrial monitoring is available in your jurisdiction, higher levels of release could entail different types of reporting (such as by phone or in person), different frequencies of reporting (for example, weekly or monthly), and different special conditions (such as electronic monitoring or curfews). When completing this task, it may benefit your team to create an inventory of your jurisdiction’s pretrial resources and services.

When deciding the conditions that will be associated with each level of pretrial release, the team should again consider the legal principles and evidence-based practices that the Release Conditions Matrix is based on. As applied to the pretrial release levels, these practices suggest the following:

- The lower levels of release should include minimal conditions, if any.

- The higher levels of release should involve some conditions and/or monitoring.

- All conditions should be the least-restrictive ones necessary to provide reasonable assurance that the person will appear at future court hearings and remain law-abiding.

During the discussion to decide on the conditions to include for each pretrial release level, the team will benefit from a basic understanding of the empirical research on pretrial risk management. A PowerPoint slide summarizing some of this research is provided in the Release Conditions Matrix Presentation, and the main points are also listed here. At a minimum, team members should understand the following:

- Research shows that court date reminders—letters, postcards, automated phone calls, personal phone calls, and/or text messages—can improve court appearance rates by approximately 30 to 50 percent. [6]

- Research has shown mixed results for pretrial monitoring and its impact on improving either court appearance or law-abiding behavior, including not engaging in new violent behavior.

- Two studies have shown that pretrial monitoring is most effective at increasing court appearances for people assessed as having a moderate or higher likelihood of pretrial failure. For people who scored as having a lower likelihood of pretrial failure, two studies found that pretrial monitoring either had no effect or had a negative effect. When pretrial monitoring was provided to people who had a lower likelihood of pretrial failure, they had the same or higher rates of pretrial failure than did similar people who were not monitored. [7]

- The studies that have examined the impact of monitoring on law-abiding behavior and public safety have failed to find that pretrial monitoring reduces arrests. One study found that there was no benefit until people had been monitored for 180 days or longer, but the authors discussed that this finding is not practically useful because judicial officers do not know how long a person will be on monitoring when ordering it as a release condition. [8]

- Studies with adequate research methodology do not show that secured financial conditions of release improve either court appearance rates or public safety. When these studies refer to secured financial conditions, they refer to cash, surety, property, or deposit-to-the-court conditions, in which people charged (or their families) must pay some amount of money before they are released from jail.

- Two studies show that unsecured financial conditions (in which no money is due before release) achieve the same court appearance rates as do secured conditions. And no study has shown that higher monetary amounts improve appearance rates. [9]

- Because in nearly all states some amount of money is typically forfeited only for failure to appear in court and not for new criminal activity, financial conditions virtually never are legally relevant to public safety. And to date, no studies have shown that secured financial conditions in any amount improve public safety. [10]

- The risk principle appears to apply to people pretrial. This principle maintains that treatment resources and other interventions directed at people assessed as moderate and higher risk will result in better outcomes; targeting lower risk people with these resources produces no benefit and may contribute to negative outcomes.

Based on legal principles and the available empirical research on pretrial release conditions, all of the examples of Pretrial Release Level tables do the following:

- Provide court-date notifications for all levels of pretrial release, including to people released with no additional court-ordered conditions (such as those released on their own recognizance).

- Reserve pretrial monitoring for people who are most likely to fail pretrial and, if resources allow, some people at high/moderate likelihood of pretrial failure.

- Exclude any mention of secured financial conditions, given a) that they trigger state and federal constitutional claims based on fundamental legal principles; and b) the lack of empirical support for their effectiveness. [11]

Additional Information

Some jurisdictions also want their Release Conditions Matrix to reflect additional information, such as the seriousness or type of charge and/or unique circumstances about a case. For instance, a person with no criminal history but charged with a first-degree violent offense may score very low on the PSA; without any additional information, the grid might place the person on the lowest level of pretrial release, resulting in little monitoring, if any. Similarly, people charged with sex offenses, impaired-driving offenses, or domestic violence offenses will receive PSA scores that predict only the general likelihood of committing any new offense or any violent offense. [12] Judicial officers may wish to individualize pretrial release conditions for these people. Given that, many policy teams make a policy decision to include guidance about which specific pretrial release conditions might help people who have certain charges or patterns in their criminal history to appear in court and remain law-abiding.. As a matter of policy, the team must decide whether to provide any such additional guidance.

By design and in practice, jurisdictions should limit the types of situations in which exceptions or deviations from the presumed release levels will be made. Otherwise, exceptions may overshadow the rule, resulting in inconsistent decisions that are not based on assessed likelihood of pretrial success.

The entire Release Conditions Matrix is a guide to help the judicial officer make the most effective and efficient use of PSA results. When deciding on appropriate release conditions, the judicial officer should take other facts and circumstances into account, such as these:

- the nature and severity of the current charges;

- information provided by the prosecutor;

- information provided by the defense attorney;

- information provided by any relevant victims or witnesses; and/or

- the person’s life circumstances (such as employment, enrollment in school or a training program, family life, or housing).

Here are questions to consider when creating a Release Conditions Matrix.

Expert trainers discuss developing an effective and research-based Release Conditions Matrix for the PSA.

Updating the Release Conditions Matrix

Once your jurisdiction is using the PSA, the policy team should meet regularly to review the system’s pretrial outcomes and the utility of the Release Conditions Matrix. The Guide to Outcomes and Oversight provides suggestions on how to measure, report, and analyze outcomes. Based on the results, the team should discuss whether the matrix should be changed in any way. For example, if the jurisdiction’s pretrial resources increase or decrease over time, the team should consider revising the matrix to reflect those changes. If the jurisdiction experiences high pretrial success rates for people at various release levels, the team may consider whether the same court-appearance and law-abiding outcomes could likely be achieved while reducing the nature and intensity of the conditions at each pretrial release level. Finally, if your jurisdiction imposes secured financial conditions, the team may want to consider discontinuing their use, based not only on legal principles and evidence-based practices, but because higher release rates for certain demographic groups (such as people of color or indigent people) could likely be achieved without them. Moreover, certain court cases may soon require jurisdictions to eliminate the use of any financial release conditions that result in detention. [13]

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Why doesn’t the Release Conditions Matrix include presumptive detention for people who have a higher likelihood of pretrial failure?

A: Whether a person can be released or detained pretrial is primarily a legal matter and is based on criteria set forth in a state’s constitution, statutes/codes, court rules, or some combination. Therefore, pretrial detention decisions should be made by a judicial officer based on these legal criteria, and only after a detention hearing in which the person charged is afforded due process. The matrix should be used only after the judicial officer has decided to release someone, and then is deciding which release conditions to order for that person.

Q: Our jurisdiction doesn’t provide any pretrial services. What do we do? Should we still create a Release Conditions Matrix?

A: Yes—even where pretrial services are limited or absent, you should still create a Release Conditions Matrix. In jurisdictions with pretrial services, these programs typically provide staff members who (1) assess, by scoring the PSA and providing the pretrial assessment report to the court; and (2) assist, by supporting people who are charged to return to court and remain law-abiding. Many jurisdictions using the PSA already had a pretrial services program or created one as part of implementation. Regardless of whether your jurisdiction has pretrial services, it will be necessary, at a minimum, for staff members from some criminal justice agency to perform the assessment function—that is, to score the PSA and report the results and other important information to judicial officers. Your jurisdiction should also consider developing pretrial supervision services for people who have a higher likelihood of pretrial failure; the extent of this assistance will be determined locally based on available resources and always within any statutory or court administrative parameters. But even where resources are severely constrained, a Release Conditions Matrix can serve a valuable purpose by helping judicial officers identify people who may be appropriate for release with no conditions, as well as others for whom greater restrictions are indicated. When creating a matrix, decision makers can choose from different examples of matrices that reflect jurisdictions with different types and amounts of resources (such as a pretrial services program). For more information, see Examples of a Release Condition Matrix.

Q: None of the example matrices refer to the use of secured financial release conditions (also known as secured money bail). Why aren’t these conditions included in the examples?

A: The examples are designed to be consistent with federal and state pretrial laws and to incorporate research regarding the most effective practices to maximize court appearance and public safety. A substantial amount of litigation is challenging courts’ reliance on financial conditions of release, and a number of recent rulings have held that current practices are inconsistent with the U.S. Constitution. Furthermore, research does not indicate that secured financial conditions of release help achieve court appearance or public safety; instead, they often delay or prevent pretrial release of people otherwise entitled to be released before trial. Jurisdictions that have implemented the PSA have demonstrated that it is possible to construct a matrix that accomplishes desired pretrial goals, is compliant with pretrial law, and does not use presumptive financial conditions of release.

Q: Does the Release Conditions Matrix operate like a money bond schedule?

A: No. A money bond schedule links charges to specified financial conditions of release. Typically, as the severity of charges increase, so does the amount of money required for release. This is based on two flawed premises that are unsupported by any reliable research—namely, (1) that the more serious the charge, the greater the likelihood that a person will fail to appear or will be rearrested before trial; and (2) that increased financial conditions of release will increase court appearance and improve public safety. By contrast, the Release Conditions Matrix is based on a deep long-standing foundation of empirical research showing that it is most effective to assign release conditions based not on charge, but on when those conditions would be most effective at ensuring that people return to court and remain arrest-free. The matrix is designed to support consistent application of release conditions based on assessed likelihood of pretrial success—in a manner that aligns with statutes and local policies and takes into account available resources. Many jurisdictions using the PSA have ceased using their money bond schedules because they interfere with achieving desired pretrial goals.

Q: Why are the release levels and conditions labeled “presumptive”?

A: PSA scores are only one part of judicial officers’ decisions about release levels and conditions. The term “presumptive” means that in the absence of any additional information, these are the release conditions local stakeholders have agreed are typically appropriate for people with particular PSA scores. But judicial officers often have access to additional information about the person or the case, information that may lead them to order release conditions different from those on the matrix. Therefore, the Release Conditions Matrix should not be viewed as providing “recommendations” but presumptive conditions of release that establish a starting point for judicial decisions.

Q: Why are certain pretrial release conditions, such as electronic monitoring, categorized as “Other Case-Specific Conditions” instead of being designated as presumptive or required for different release levels?

A: Those release conditions should be used sparingly if at all—and only when a judicial officer has reason to believe they would be effective in improving a specific person’s pretrial performance. In addition, there is minimal empirical research to support the pretrial effectiveness of the conditions that could be included under Other Case-Specific Conditions, which often place a heavy financial burden on the local justice system (or on people charged if they are required to pay for the conditions). They also place a heavy practical burden and restriction on the liberty of people.