Guide to Community Engagement, Part 1

Understand the value of community engagement and complete a self-assessment to gauge your jurisdiction’s capacity to do this work.

Introduction

Community engagement is an important process to help your team advance equity and other positive changes in your local pretrial system. Community engagement seeks to meaningfully incorporate people’s interests, solutions, and values in decisions and actions on public matters.

What Is Community Engagement?

Community engagement is intended to build relationships both 1) among citizens and organizations and 2) among citizens. By “citizen,” we mean anyone who is a resident of their community (regardless of their legal status) or a stakeholder affected by the criminal legal system.

The best engagement is rooted in an understanding of a community’s historical traumas and triumphs. Through deep listening on a regular basis, engagement seeks to build a partnership that contributes to meaningfully incorporating people’s voices and values in decisions and actions on public matters.

Engagement is meaningful when people can work with one another to learn about issues, understand others’ views, address equity and differences, generate ideas, and make plans for action. It is rare to accomplish all of those things in one setting. That is why engagement must be sustained and systemic, not a sporadic series of one-time activities.

Community engagement centers on the belief that everyone has the right to be involved in decisions that will affect their life.

Engagement happens in person and online, in small- and large-group settings, in a few minutes and over a number of months. Engagement may involve modest participation, such as visiting a website or an open house, or deeply collaborative participation, such as serving on a citizen advisory group or a jury.

Community engagement can help address many of the challenges criminal legal system leaders experience in their work—including understanding the perspectives of people impacted by the system, addressing the gaps in racial equity, communicating their agencies’ commitment to public service, and building relationships they can draw on regularly and in times of crisis. The process of engagement will succeed only with trust, which is earned and developed over time as a result of consistency and results.

Importance of Authentic Engagement

Unfortunately, some government agencies and other organizations have traditionally engaged communities as a public relations campaign rather than as an authentic way to understand and act on community input. When organizations invite the community to participate mainly for optics or to get community buy-in on a decision they have already made, this can be problematic because they are not really asking for the community’s collaboration or opinions. This kind of engagement doesn’t improve systems or policies and may diminish rather than increase people’s trust.

Some organizations also have a history of extractive engagement—that is, they ask many questions of a community but don’t follow through by sharing how their input was used or including them in meaningful collaboration. This may lead to members of the community feeling that they can’t trust the organization or the system.

Who Is the “Community”?

Community can be defined as many types of stakeholders, such as people living in a neighborhood served by your criminal legal system agencies, those who work in the pretrial system, local business leaders, survivors of crime, and people who are system-involved and their families. All of these communities are important.

There should be engagement within your system that reflects input from people at various levels of responsibility in your agencies; a patrol officer or a custodian in a jail will have different perspectives than a sheriff or a jail administrator. All of these perspectives can help improve pretrial systems.

There is also a need for engagement outside the criminal legal system. It is common for public officials to think of engagement outside the system as being with “community partners,” such as substance use treatment centers, mental health care providers, and other nonprofit entities that help serve people pretrial. These partners can be extremely helpful, but engagement should be expanded to involve a broader range of community members, including survivors of crime and people who are system-involved and their families.

People who are system-involved and their loved ones are often overlooked when we use the term “community.” But they have valuable information to share about how pretrial services were—or were not—effective for them. They can share how the pretrial system may unintentionally cause additional harm, including the loss of employment, childcare, housing, and other financial hardships. They may also be able to offer deeper insight into why certain offenses happen and which community supports and services might deter that type of behavior from occurring in the first place or from happening again.

If agencies work more collaboratively with people from the communities most affected by poverty and crime, the organizations may take steps toward undoing the racism that is inherent in our criminal legal system, including our pretrial system.

The Value of Community Engagement

Engagement directly benefits communities and can lead to more effective and equitable systems. Establishing meaningful partnerships between system stakeholders and the community to examine pretrial policies and practices—and implement better ones—is the first step in making a pretrial system fairer, more just, and more effective.

Engagement can also help you do the following:

- Have a better understanding of people who are system-involved—and their families and communities—including the successes they experience and the challenges they face

- Improve communication among staff members (by including more of them in expanded engagement processes)

- Improve communication between your pretrial system and the community

- Provide valuable supports and services for people impacted by the system and their loved ones

- Enhance community support for your pretrial system

Better Policy

When people come together in well-structured processes—including ones that allow them to talk in small groups about what they have learned and what they recommend—the resulting policies and plans are smarter, are more broadly supported, and better reflect what citizens want.

Listening to and including community members—especially those who are most impacted by policies, such as survivors of crime and people who are system-involved (and many people are both)—as part of a decision-making process can help identify potential issues with current policies and the design of new ones, and ultimately make them more effective.

Community engagement can lead to better policies in simple yet effective ways. At one jail in a midwestern city, conflict was common between those coming to visit their loved ones and the employees running the metal detectors and sign-in sheets. This resulted in long lines, some denials of entry, and extremely upset people in the facility and beyond.

The jail used community engagement as a strategy to identify the problem: they asked the community how the jail could improve the visiting process. Through this exercise, two fixable issues surfaced. First, the instructions were all in English, causing difficulty for some people whose first language was not English. Second, the policy of asking for personal identification raised concerns among those who may not have had an acceptable form of identification or who may have been unsure about how their information might be used. Being asked for ID and not understanding the language was especially anxiety-inducing for people from immigrant communities.

After understanding these issues, the jail changed its intake processes by reproducing the forms in multiple languages and clarifying the purpose of showing ID and which types were acceptable. The lines and conflict involved with visitation soon dissipated.

Moving Toward Equity

Structural racism, socioeconomic disparity, unequal opportunity, and other factors have shaped our communities and the nation. Community engagement establishes a path toward equity. When people with diverse backgrounds and points of view learn from one another and work together, the outcomes tend to be more equitable and responsive to a broad spectrum of community interests. Not all communities are the same, so engagement should focus on the cultures of your communities.

Community engagement may include providing more opportunities to develop mutual understanding, collaborate on creating policy, and build relationships between your pretrial system and the public. If done authentically, it can contribute to more equity in the criminal legal system overall.

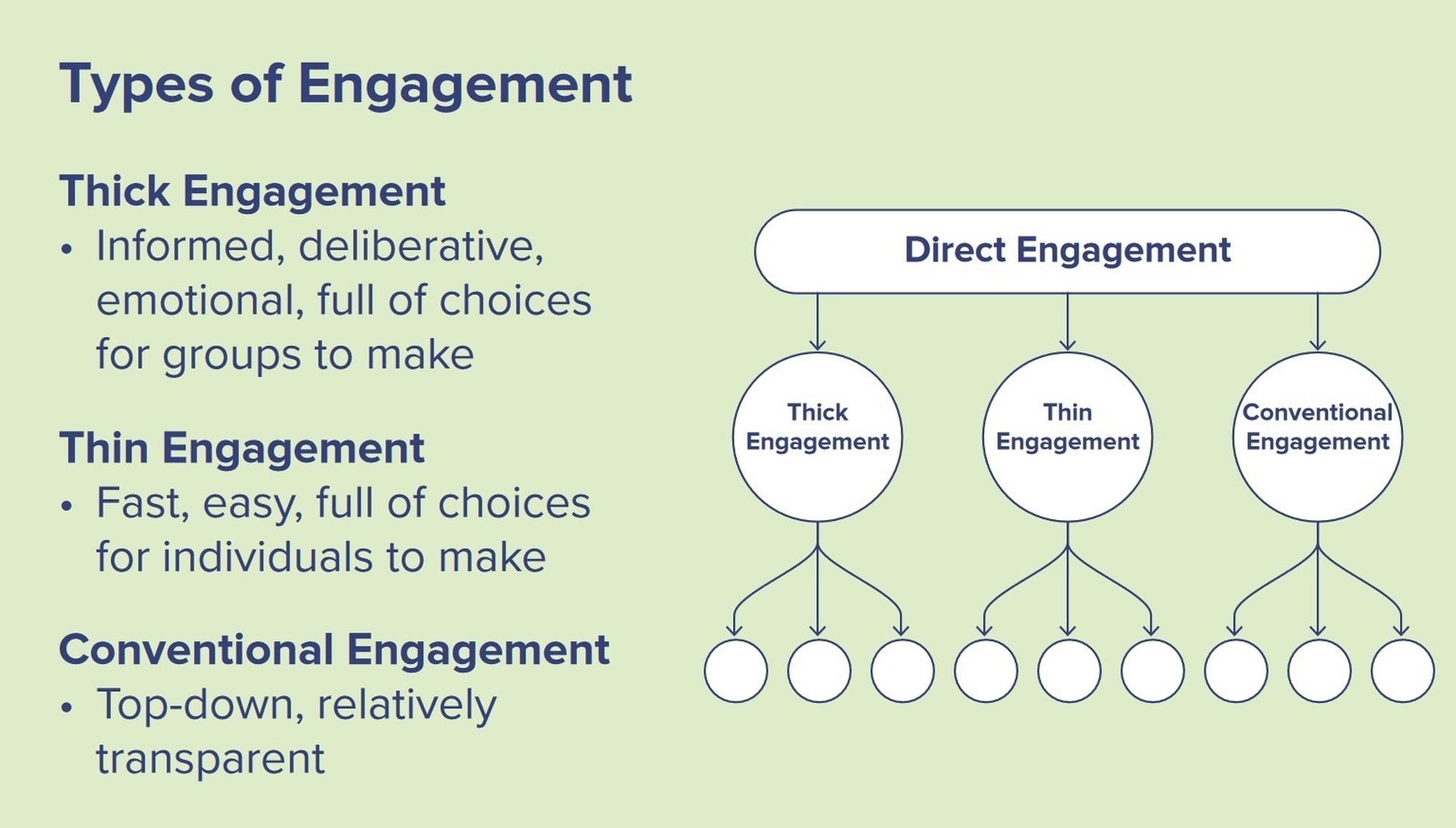

Three Main Types of Community Engagement

There are three major categories of engagement: conventional, thick, and thin. These types of engagement have different strengths and limitations, and they complement each other well. All of them can be part of an effective “multichannel” approach to engagement. You’ll need methods to engage people in deep, substantive ways and others that are quick and can reach a lot of people. By using all three types, you can create multiple levels of engagement to accommodate people when they are available—and ideally generate more interest in participating.

As you review the categories, ask yourself these questions:

- Which types of community engagement are you using in your work now? Which ones might you want to try?

- How might you alter your conventional activities to be thicker or thinner?

Conventional Engagement

Conventional engagement is what happens in most public settings. For example, let’s consider the typical “town meeting.” System stakeholders convene the meeting, where citizens and officials are physically separated from one another, frequently by a podium. There are no breakout sessions or small-group discussions, and citizens have brief opportunities (often limited to two or three minutes) to address the whole group. Public officials rarely respond directly to the public’s comments.

The main goal of this kind of engagement is typically to get comments on the record and not necessarily to have a meaningful two-way conversation. The physical layout of these meetings usually puts officials in an elevated position, such as sitting on a stage, separated from the community and reinforcing hierarchy. These settings and processes are highly structured by design.

Conventional Engagement

Pros: Easier for public officials to manage; a familiar setting

Cons: Doesn’t involve the community in a two-way conversation; reinforces power dynamics; does not allow for deep listening

Public officials often lean on conventional engagement because they may believe that a rigid structure allows for more control over the process. But not engaging the public in more collaborative, reciprocal ways may ultimately make people displeased with the process, and, in turn, they may become angry or disengaged, which may lead to additional mistrust.

Although conventional engagement as described has its limitations, it can be made more effective. You can make it “thicker” by providing opportunities for small-group discussions or “thinner” by supplementing it with online polls.

Thick Engagement

Thick engagement is more intensive, informed, and deliberative. Although hundreds of people can participate in a thick process, most of the action happens in facilitated small-group discussions. Organizers of thick engagement processes assemble large numbers of diverse people, give participants chances to discuss their experiences, present a range of views or policy options, and encourage action and change at multiple levels. Thick engagement takes time, anywhere from several hours to months.

A community dialogue is one example of thick engagement. Other examples include community advisory councils and similar groups whose members commit to meet over time. People talk in small groups of 10 to 15 people about an important issue or decision that needs to be made. An impartial person trained in facilitation leads the group through the process. People in each group have many opportunities to share, talk with each other, and respond to questions from the facilitator. The facilitator helps guide the process so that everyone gets a chance to speak, people share airtime, and disagreement remains productive and not volatile. The phases of a dialogue move from brainstorming to digging into key issues, problem solving, and determining key priorities.

Thick Engagement

Pros: Information gathered is deeper, more informed, and more detailed

Cons: Time-consuming; challenging to organize

This kind of engagement means managing a lot of logistics, and the time commitment can be a challenge for some people. Recruiting community members to participate is key and can take time, but it is essential so that you attract people beyond the usual stakeholders and community members.

Some agencies have a budget to compensate community members for their participation in engagement activities. Consider doing this in your jurisdiction and securing or earmarking this type of funding in the future.

Thin Engagement

Thin engagement is faster, easier, and more convenient than thick engagement. It includes a range of activities that allow people to express their opinions, make choices, or affiliate themselves with a particular group or cause. It can happen face-to-face, such as asking someone to sign a petition, but more commonly takes place online, via telephone, or through apps.

Thin engagement can capture a wide audience in a short period, but it is limited in the depth of information that can be shared and gathered. Quick opportunities for input—like public comment or voting—may also be considered “thin” because they are fast, allow many people to participate, and don’t require individuals to delve too deeply into nuances or trade-offs. Thin engagement doesn’t typically encourage people to consider the views of others carefully.

A familiar example of thin engagement is a survey. Surveys can be sent to thousands of people simultaneously so that they can respond quickly and at their convenience. But the amount of information you can receive from each person is limited.

Thin Engagement

Pros: Faster, easier, more convenient; can engage a wider audience

Cons: Limited in the depth of information that can be shared and gathered

Reflecting on Where You Are

If you’re relatively new to community engagement or your jurisdiction has limited experience with it, you will want to gauge the capacity you and your colleagues have to do this work. Engaging in a self-reflection exercise will help you identify what assets you have to build on as well as where you’ll need to expend more effort.

Community Engagement Self-Assessment

The Community Engagement Self-Assessment was developed by Everyday Democracy and adapted by Public Agenda for APPR. It is intended to encourage discussion and reflection among people who are interested in beginning or improving their jurisdiction’s community engagement as part of their pretrial improvement process.

You can use the self-assessment in a variety of ways, depending on the needs of your jurisdiction’s stakeholders and dynamics. If you are interested in beginning community engagement, it can help identify what steps to take before launching your efforts. If you are already working on community engagement, this self-assessment can help you reflect on your progress and identify what you still might need to address.

The assessment takes stock of your policy team’s work in three areas:

- Capacity and support: The staff time available to conduct community engagement activities and the level of understanding of participating agencies

- Communication: The quality of correspondence and other dialogue within agencies as well as between and among agencies, constituents, and those who are most impacted by the pretrial system

- Partnerships and planning: Any partnerships and collaborations between and among the criminal legal system and community organizations, along with future work those groups expect to do together

The assessment includes instructions on how to complete the tool, as well as guidance on how to understand the results and identify next steps. You may decide to complete the assessment as a group at a subcommittee meeting or you may ask individual members to complete the tool before you convene.

Key links

- See our recorded Community Engagement Trainings Link