Guide to Community Engagement, Part 2

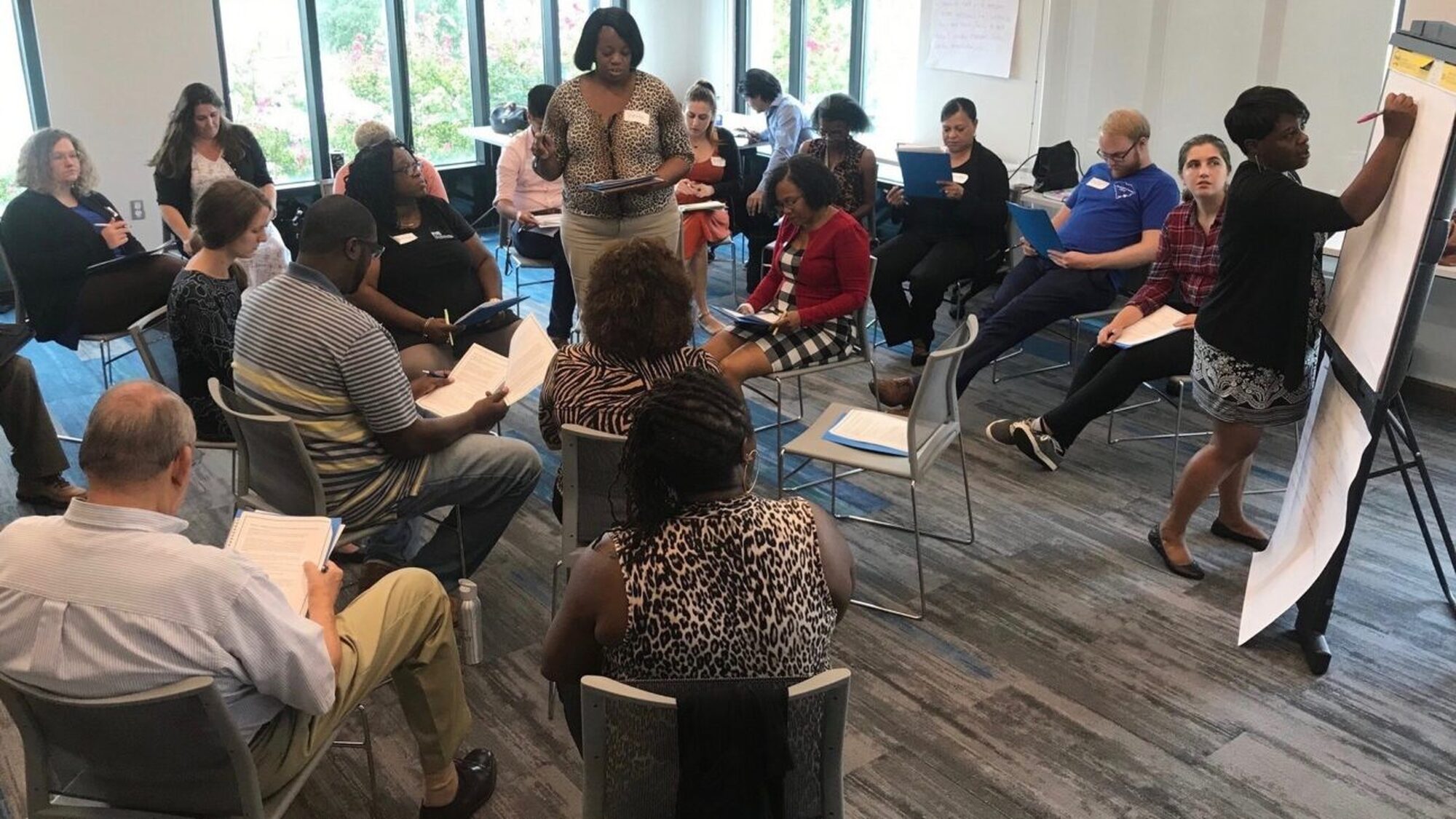

Identify different types of community engagement activities and consider which activities are most effective for different purposes.

Introduction

Community engagement is an important process to help your team advance equity and other positive changes in your local pretrial system. It seeks to meaningfully incorporate people’s interests, solutions, and values in decisions and actions on public matters.

If you have completed the Guide to Community Engagement Part 1, you will have evaluated the capacity you and your colleagues have to do this work. Now you are ready to design a comprehensive engagement strategy. This guide walks you through the steps your team can take to approach and expand community engagement.

Exploring the Spectrum of Engagement

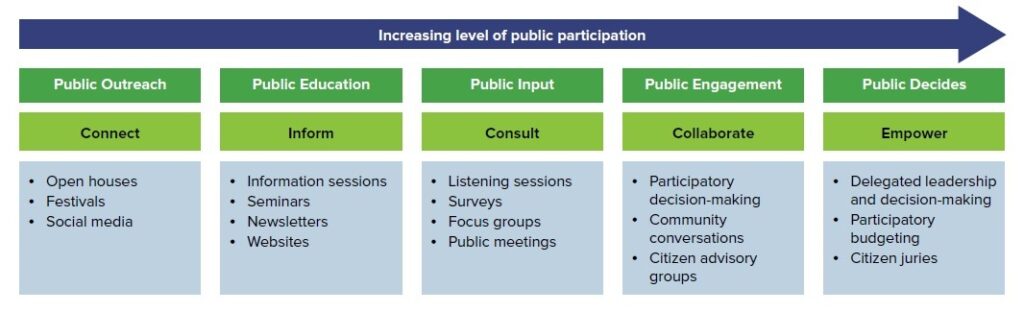

Engagement occurs in many forms, on a spectrum ranging from outreach activities like open houses and festivals to deeper processes like participatory budgeting and citizen juries. The activities you plan will depend on your reasons for engaging the community. For example, as the spectrum of engagement demonstrates, certain activities educate the public while others gather community input.

Adapted from the International Association for Public Participation’s Spectrum of Public Participation.

Here are some examples in the pretrial context:

- Public education: Your policy team or stakeholder group has decided to update the pretrial screening process and you want to inform people about these changes before launching them.

- Public input: To help improve the court-reminder process, you want to hear from people affected by the system about their experiences with that process.

- Public engagement: You want people to contribute to policymaking and be part of the decision-making process for identifying supportive pretrial services.

Deeper community engagement is represented mostly by activities on the right-hand side of the spectrum. But sometimes you may need to structure engagement processes to draw on a range of approaches. For example, you might pair public education with public engagement so that the community can learn about a concept, such as pretrial improvements, as well as identify ways that people can respond to the issues at hand.

In-Person or Online Engagement?

When the COVID-19 pandemic began, people increasingly turned to online approaches for engaging with the community. Contrary to what you may think, thick and thin engagement can happen both in person and online. Online discussions can be excellent for generating and sustaining engagement. They can provide convenient, information-rich settings for people to connect, have meaningful conversations (including small-group discussions), make decisions, and develop plans for action, just as in-person interactions can. But to ensure the success of an online discussion, you need a thoughtful moderator, just as you need a skilled facilitator for many face-to-face conversations.

Even in “normal” times, online discussions have advantages. Holding conversations online enables you to connect with more people than you could in person. Online discussions also have the potential to bring together people from vastly different places. Choosing an online venue means fewer logistics to worry about, and it can be more convenient for participants who would otherwise be unable to attend because of transportation, childcare, or other demands.

Another benefit of online engagement is that it can be synchronous or asynchronous. In synchronous discussions, all participants communicate simultaneously or read each other’s comments as soon as they are posted. In asynchronous conversations, participants aren’t expected to be engaged at the same time; their discussion may play out over many days or weeks.

Facebook Live and Zoom convenings are synchronous, while a Twitter thread and online discussion boards/forums are asynchronous. An asynchronous conversation further accommodates those who are strapped for time or unable to participate for long periods. But an asynchronous conversation needs close and careful moderation in order to maintain momentum.

Challenges of Online Moderation

Online engagement isn’t perfect. When people can’t see others’ faces, they may be more likely to say careless things and be less mindful of how their statements are being perceived because they can’t interpret others’ reactions. This can be especially true when people are participating anonymously. You may be able to minimize these problems by using platforms that require real names and encouraging the group to adopt ground rules about civility and empathy.

It is also much more difficult to guarantee the attentiveness of participants in an online discussion. Because people are usually looking at a screen during the conversation, they may be distracted by incoming emails, pop-up windows, and other diversions. This doesn’t matter in an asynchronous discussion, but to keep momentum going in synchronous forums, the moderator may need to interact more deliberately, such as asking questions of the group or calling on members who aren’t contributing.

Another related challenge in moderating an online discussion is that it can be harder to “read the room” because people’s physical cues are more difficult to see and interpret. In person, you might observe how someone appears as they enter the room and which comments they are nodding in agreement to—or which ones make them look confused. Check-in questions can help you figure out how participants are feeling and responding.

Community Engagement Case Studies

Read these stories of community engagement:

- The Dane County Criminal Justice Council (CJC) is engaging community members “to shorten the gap between government and community,” says Colleen Clark-Bernhardt, the CJC’s coordinator. Read the CJC’s story.

- Since the inception of Charleston County’s Criminal Justice Coordinating Council, “community representatives have been at the table informing its efforts,” says Susanne Grose, system utilization manager for the council. Read the case study.

- Residents of the Centro Barrio neighborhood in Tucson, Arizona, collaborated on a project to define what safety means to them. Read a Q&A with the director of the Reframing Justice project.

- In 2010, New Orleans had the highest urban incarceration in the country. Read the case study about how community engagement helped reshape the pretrial system and dramatically reduce the jail population.

Ask yourself these questions as you read the stories:

- What activities from across the spectrum of engagement did these jurisdictions employ?

- Given the circumstances in our jurisdiction, what activities might be most appropriate for us to consider implementing?

- What community engagement activities employed by these jurisdictions align with our pretrial improvement values and goals?

Key links

- Taking the Conversation Virtual External Link

Developing Your Community Engagement Strategy

You may develop your community engagement strategy with the assistance of a policy team, a subcommittee, or an informal group of involved stakeholders. The process you decide upon will depend on your jurisdiction and its circumstances. It is recommended, however, that you update your policy team throughout the process and make sure you have its support for the engagement activities.

Use APPR’s Community Engagement Strategy Template (DOC) to help you get started. As you complete the activities described in the subsequent pages, fill in the basic details about your engagement strategy.

Getting Started

For many engagement strategies, you will identify your jurisdiction’s goals before getting into great detail about the community you want to involve. At other times, you may identify a community or communities to engage before you determine specific goals.

Identifying Your Engagement Goals

Your first step in creating an engagement strategy may be to identify your goal(s) for community engagement. You may refer to the spectrum of engagement on page 2 for this activity.

Goals often correspond to a problem you want to solve or a process you hope to strengthen. Here are some examples of community engagement goals:

- Build support for a program by informing the public. You have important information to share with people about a new pretrial program. You hope to find the best formal and informal channels of communication to spread this message and build support from those who will be most interested in and affected by the program. Achieving this goal will require public outreach and possibly public education.

- Strengthen an existing program. Your jurisdiction has a court reminder system, but it isn’t working as well as hoped. Sixty percent of people who need to appear in court do not use the current system, with non-English speakers and people with disabilities overrepresented in that group. You want to incorporate input from community members, especially those two subgroups, about how to make reminders more effective. Achieving this goal may require public input and engagement.

- Build more trust between the criminal legal system and historically excluded communities. In countless ways, a long history of racism has played out in criminal legal systems and beyond—including economic and racial segregation and disproportionate arrests, sentencing, and incarceration in Black and Latino communities. You want to bring criminal legal system stakeholders and the broader community together to acknowledge this history and build trust. Achieving this goal will probably require the public’s input, engagement, and, potentially, decision making.

- Develop a program that helps advance the interests of the community through collaborative decision making. Let’s say that substance use and related arrests are on the rise among Black men in your community. You want to create a harm reduction program in partnership with local leaders, other members of the community, and pretrial staff. Achieving this goal may require public input, engagement, and decision making.

Setting Your Goals

As you establish your goals, consider these questions:

- Would it be helpful to have public support of the changes you are proposing? How might the public help implement the new programs or policies?

- Could public input help shape and improve pretrial policies and practices?

- Do you need to address past criticisms of the policies and practices related to your goal and make changes that reflect those responses? Similarly, what criticisms do you anticipate going forward, and how might you address them?

- Can you identify leaders or groups that could be partners in this work? Are some of those people within your organization? If not, what is the best way to reach out to colleagues and other community members?

While setting your goals, think about whose input you need to help prioritize them:

- Are there opinions not represented on your policy team?

- Do you have input from leaders with decision-making power?

- Would it help your policymaking process to hear from people who have direct experience going through the pretrial system?

Identifying the Community You Are Engaging

Once you have concrete goals in mind, focus on the community you most want to engage. This will help inform how you choose to engage. But who is “the community”?

It may seem obvious, but the community is made up of the people your pretrial system serves, as well as other individuals and groups that serve them. That means not just people who are system-involved, survivors of crime, and their respective families but also local businesses, social service providers, faith communities, local activists, young people, elected officials, schools, and other important stakeholders in your jurisdiction. You may need to intentionally engage all of them.

When thinking about community engagement in your pretrial system, you would ideally engage all of these groups in some way. But in a world of limited time and resources, consider the value of creating authentic, meaningful opportunities for collaboration—ones that amplify the voices of people who have been historically excluded in decision making due to structural racism and other forms of discrimination.

Engaging Historically Excluded Groups

When considering how to conduct engagement around pretrial practices, remember the mantra that the disability rights community popularized: “Nothing about us without us.” For a long time, decisions have been made that affect communities without their members’ meaningful consultation. This often leads to policies and practices that are inequitable and unpopular, further straining the relationship between decision makers and the community.

Black people and Latinos are overrepresented in the criminal legal system but are often underrepresented in decisions made about the system and in community engagement processes. Creating opportunities to collaborate with the community moves the system toward equity. Another key aspect of equity is intentional and vigorous outreach to diverse audiences. Without such outreach, you are likely to attract the usual participants, and in many communities that means people who are older, wealthier, white, and more advantaged.

“Nothing about us without us is for us.

When deciding whom to engage, remember to ask yourself these questions:

- Are there opinions or perspectives not represented on our policy team?

- Whose input might be valuable to help us achieve our goals?

- How can hearing from survivors of crime or other people impacted by the system strengthen our pretrial system?

Deciding on Engagement Activities

After figuring out what your goals are and whom you want to engage, you’ll need to determine how you will engage the community. You will want to consider the following questions:

- Why are you engaging the community at this time?

- What role do you intend the community to play in your work?

- Based on your goals, are you prioritizing reaching large numbers of people? Or will you go deeper with a smaller group of people?

- What types of engagement might work best with your target audience(s)?

- Is your audience technically proficient enough to use certain tools (especially online)? Do people have access to those tools?

- Can you safely organize in-person meetings?

- Do you plan to collect data from participants (by polling, collecting contact information, or some other means)? Are you prepared to record participants’ comments?

- Once activities have been completed, how will you follow up to show people their impact on the process?

Selecting Engagement Activities to Support Your Goals

Now you’ll want to spend some time thinking about how to select activities to support your goals for working with communities. You may want to have another look at the spectrum of engagement to refresh your memory about the types of activities.

Surveys (Thin Engagement)

Surveys usually take the form of a questionnaire and can be a good way to gather public input. They can be formatted in multiple ways and can be administered in person, by phone, or online. You can use surveys as part of your engagement strategy to seek public input on a variety of topics, including the decisions and initiatives that will affect people and their communities.

Listening Sessions (Thick & Thin Engagement)

A listening session is a facilitated discussion with a group of people on a specific topic. It is another way to get public input and engage community members, and it may involve or lead to public decision making. You can use this activity to enable community members to share their experiences, thoughts, and ideas with you and one another. You can also use it to obtain feedback from the community about specific programs or initiatives. It is a hybrid form of engagement that combines thick and thin elements. Listening sessions can be structured in different ways. If the idea is for participants to drop in briefly to give a comment or cast a vote, this activity would be on the thinner end of the engagement scale. If the listening session is focused on small-group dialogues, it becomes thick engagement.

Visual Timeline Exercise (Thick Engagement)

A timeline can serve as a visual tool to assess how your agency has engaged community members in recent years. This exercise can be a way to do public education, gather input, and/or engage the community; you can do it with your team or with a larger group of people from the community. The steps are as follows:

- Create a timeline that starts years in the past and ends with the present. You can divide the years into one-year intervals, five-year intervals, or decades.

- Brainstorm with your group all of the engagement efforts your team has facilitated—and/or that you know about—and enter them where they belong on the timeline.

- List how many people were engaged in each effort and briefly describe who participated (e.g., pretrial services staff, police officers, survivors of crime, people who were arrested in the past, family members, local business owners, treatment providers).

- Give people time to review the timeline. Use colored markers and ask people to list positive aspects of each effort using one color and negative aspects in another.

The timeline can help you reflect on which events and efforts were well-received and which could have been improved. You can also use it to list and assess engagement opportunities that other organizations have offered, including efforts by the police, schools, planning departments, businesses, nonprofits, neighborhood associations, community organizers, and local elected officials. All of these activities contribute to how residents experience engagement: Did they value certain engagement opportunities more than others? Did they feel “burned” in some situations because they participated but didn’t feel heard? Past events—both positive and negative—are resources from which your team can learn and grow.

World Café Method (Thick Engagement)

This method can be used for large-group dialogue, also involves small-group discussions (thick engagement), and is probably most closely associated with public input, engagement, and decision making. World Café adheres to these interconnected steps and principles:

- Set the context.

- Create hospitable space.

- Explore questions that matter.

- Encourage everyone’s contribution.

- Connect diverse perspectives.

- Listen together for patterns and insights.

- Share collective discoveries.

You can read more details about the principles and how people use this method on the World Café website, which describes this activity as “simple and simple to learn,” though an experienced facilitator or “host” is recommended.

Advisory Council (Thick & Thin Engagement)

An advisory council is a collaborative engagement structure that works to provide advice to an agency or program. These councils are structures that conduct engagement activities, so they are a little different from other approaches listed here, but they can be helpful in the context of the criminal legal system. Some advisory councils might last only in the short term, such as when working to plan one event, while other councils may be sustained groups that work over time with a criminal legal system agency, such as a police department. On the engagement spectrum, an advisory council involves public input, engagement, and decision making. This group can serve as a critical community champion for the goal of implementing and strengthening engagement between your pretrial system and the public. Members of the group provide value by sharing their personal and/or professional expertise, diverse knowledge and perspectives, and connections to local resources, including those in the communities you want to engage. An advisory council can help guide you on the design, implementation, and evaluation of community engagement. It is also a hybrid form of engagement that can include thin and thick activities.

Considering Accessibility and Inclusion

When organizing the activities, be sure to think about accessibility:

- Timing: Be mindful of when you hold events. Are they during the day and the evening, to accommodate different schedules? Can you record the activity so that people who can’t attend may listen later and at their own speed?

- Location: Think about where you will hold events. Choose a location that is welcoming (or at least neutral); compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act, like a library or rec center; and not intimidating, as a courthouse or county office building might be.

- Transportation: Will participants experience transportation issues? Can you provide stipends for public transportation?

- Payment: Participants are contributing their expertise and time to the activity. Can you compensate community members for their participation in engagement activities?

- Language: Language barriers can be a serious obstacle to participation, so you may want to consider having interpreters, including American Sign Language (ASL) interpreters, and/or having written materials translated as needed.

You should also think about inclusion:

- Will your event be family-friendly, so that elderly adults, young people, and families with children can attend? Consider providing childcare and refreshments.

- Can you provide resources that allow people to fully participate (such as an ASL or other language interpreter, sufficient amplification, and live captions for digital events)?

Remember that you should plan engagement with your community in mind. This process is about your relationship with them. Be realistic about where your relationship stands with community members. If you have never hosted a listening session with people of color about issues of race, think about beginning gradually and with small steps (and not, for example, starting with a citizen advisory council that focuses on racial issues). Take the time to nurture trust with new or complicated relationships, and capitalize on your strongest relationships to help move you to deeper types of engagement.

Recruiting for Community Engagement

In engagement, both diversity and numbers matter. The more people you involve who provide diverse perspectives, the more successful you are likely to be. When engagement involves a broad cross-section of the community, it is more likely to benefit the community as a whole, and when there is a diverse mix of participants, the interactions will better represent community interest overall and may be more rewarding. When we say “diversity,” we mean a mix of ages, races, ethnicities, genders, and other identities; we also mean a mix of opinions and experiences. To attract a large number of diverse people, carefully consider what you will need to plan a great experience for them.

Creating Outreach Plans

“Recruiting” might seem like an unusual word in the context of community engagement, but that is really what you are doing! Just as you would recruit for a team, you are trying to get people to participate over the long term in activities related to strengthening the pretrial system. The intensity of people’s commitment may vary, but again, you are working toward a sustained system of engagement. The activity you are planning now is just the beginning. The effort you put into recruiting will be worth it.

These five steps can help you review what you’ve done so far and develop an effective outreach plan.

- Review your outreach goals. By now you should know whom you want to engage. How many people need to be involved in each activity to give the effort a critical mass? What kinds of people are needed for diversity, broadly defined? Do particular groups need to have a voice in the process? Why would people from each group want to participate? What kinds of barriers might keep people in each group from participating in an activity, and how might you address those barriers? Is there another group you can partner with to help you recruit people?

- Develop talking points. Give people a brief overview of why they might engage in the planned activity. Describe the problems or opportunities you want to address. You might also mention what supports will be available at the meeting to incentivize participation (such as food and childcare). Use clear and consistent messages.

- Plan outreach strategies. Personal invitations—offered face-to-face, by email, or by phone—are almost always more effective than flyers, ads, mailers, or social media posts. People are more likely to come to events because someone they know invited them. Ask people who are doing outreach to reach out personally to others they know and to make sure they ask them to do the same.

- Give team members recruiting assignments. Ask your partners to reach out to people in their networks. Set specific recruitment goals for each member.

- Take extra steps to reach historically excluded groups. When possible, find a spokesperson or leader in specific communities who can help spread the word. Building relationships is key to involving underrepresented groups; it’s not just about reaching out but also about creating deeper relationships with people in the communities you seek to engage who can mobilize others. Sometimes you can find these community leaders in seemingly unexpected places, such as barbershops, restaurants, or other local businesses—or at the community prosecution unit, community court, or one-stop center. Other places to find these leads might be faith-based organizations or community-serving sororities and fraternities.

Complete a Stakeholder Tree

The purpose of the Stakeholder Tree Exercise is for team members to visualize a range of stakeholders in your community and concentrate your thinking on outreach. Begin the exercise by identifying every type of stakeholder you hope to engage, then brainstorm partners that could help you reach them. Try to identify partners you already know and potential partners you don’t know but would like to build relationships with. Whenever possible, name specific people and organizations.

When you complete the exercise, consider these questions:

- Of the populations you brainstormed, which people are most affected by the pretrial system?

- Did your list include people who have been directly involved with the criminal legal system in some way? If not, consider adding them to your list.

- Did your list include people who work in the pretrial system, including people at different levels of responsibility and power? If not, consider adding them to your list.

- As you think about your goals, will you rely on other agencies beyond the criminal legal system to accomplish them? Consider adding those agencies to your list if you haven’t already.

- How will you find the people you want to work with? Who will help you find them?

Community Engagement Follow-Up Tasks

If you haven’t already, start updating your policy team about your community engagement strategy and involving team members in planning the engagement activities. You may need to educate your policy team about community engagement and explain why you identified certain audiences and chose certain engagement activities.