Illinois’ success in passing the Pretrial Fairness Act, which eliminated money bond and reshaped pretrial justice, owes much to a broad-based coalition that spent years organizing and advocating for justice. This coalition included advocates for social, economic, and racial justice, faith-based groups, victims’ rights supporters, community groups, and the people, families, and community members most impacted by the criminal legal system.

The Coalition to End Money Bond (Coalition) and the Illinois Network for Pretrial Justice (Network) formed two public-facing partnerships to coordinate activities focused on ending the use of money bond and advancing pretrial justice. The Coalition focused on driving change in Cook County (Chicago), and later launched the Network with partners in other counties to expand its work statewide.

Voices Rising in Community

The origin of pretrial activism began in the Black community, says Tanya Watkins, former executive director of Southsiders Organized for Unity and Liberation (SOUL). In churches and community meetings, people shared their stories about spending months and years in jail because they could not afford a money bond. But they were not the only people impacted by the system to come forward.

“An unfair pretrial system or unfair criminal justice system impacts all of us, and it deeply impacts more people than we envision,” Watkins said. “I am actually a harm survivor, so having the opportunity to work with others who survived harm and who recognize this system doesn’t keep us safe was vitally important.”

As communities made the injustice of pretrial practices visible, others in Cook County, a large urban county that includes Chicago, prioritized this work. Some groups provided direct services and paid bonds for people who could not afford it. Others conducted research and wrote policy briefs.

By 2016, many recognized the value of a formal collaboration to leverage the full power and expertise of these numerous organizations, and they formed the Coalition to End Money Bond.

From Organic Activism to Formal Collaboration

Successful coalitions that are formally structured and public-facing can harness diverse expertise and skills and reach a broader public audience by bringing their unique constituencies to an issue.

However, there can be barriers to collaboration. Groups may disagree about specific tactics or outcomes, have concerns about competition for funding or attention from media and the public, or have limited capacity to contribute staff time and resources.

The Coalition to End Money Bond started by articulating the Principles of Pretrial Reform in Illinois, which would unify members to work cooperatively toward the agreed-upon goals.

“We took it incredibly seriously. We tried to bring people along and have lots of discussions [to build consensus,]” said Sharone R. Mitchell, Jr., who led the months-long process of drafting the principles. Mitchell was with the Illinois Justice Project when the Coalition was formed and is now the Cook County Public Defender.

“An unfair pretrial system or unfair criminal justice system impacts all of us, and it deeply impacts more people than we envision.”

The principles gave the Coalition its foundation. While member organizations could continue to pursue individual priorities, they committed to aligning their work and messages with mutual principles when addressing pretrial reform.

“Many of us had different political lenses or theories of change as to how we were going to reach our goal and what things might look like after we got rid of money bond,” said Matthew McLoughlin, campaign coordinator, Illinois Network for Pretrial Justice. “We spent a long time talking through what our shared values were and our shared vision for pretrial reform. There were definitely differences between organizations, but we wanted to set a foundation that we all adhered to.”

Starting Local

The Coalition to End Money Bond focused on reducing pretrial detention and the use of financial release conditions in Cook County. As the Coalition began to advocate change, legal advocates filed a class action lawsuit claiming the county’s use of money bond was unconstitutional. By 2017, the litigation and advocacy contributed to the Cook County Circuit Court issuing General Order 18.8A, which created a process for judges to follow state law that indicated monetary bonds should only be set in amounts that people could afford. The order did not eliminate the problems with using money bond, but, along with changes to the staffing and structure of the county’s central bond court, it did contribute to a reduction in pretrial incarceration. However, it only applied to Cook County.

“We kept getting outreach from people in other Illinois communities who wanted to work on this issue. [Local officials would say,] ‘That’s not a problem here. That’s a Chicago problem.’ But when we talked to people involved in the court system who had loved ones arrested and in jail, we found it was actually a much worse problem in a lot of ways,” said Sharlyn Grace. When the Coalition formed, Grace was a volunteer member of Chicago Community Bond. A few months later, she joined the staff of Chicago Appleseed Center for Fair Courts, where she helped staff the Coalition for several years. She is now a senior policy advisor at the Cook County Public Defender’s Office.

Building a Statewide Coalition

The Coalition launched the Illinois Network for Pretrial Justice with new partner organizations to expand advocacy statewide. While the Coalition continued its focus on Cook County pretrial practices, the Network would include groups outside of Cook County plus all members of the Coalition.

To grow its base, the Network needed to make it easy for groups to engage. Organizations outside large urban areas may be smaller, lack the funding their urban counterparts have access to, and have less capacity.

To join the Network, groups needed to endorse the Principles of Pretrial Reform, commit to conducting two community events per year, and attend 75 percent of the Network’s monthly meetings to ensure they were plugged into the work. Today, the Network includes 31 organizations plus 14 members of the original Cook County-based Coalition.

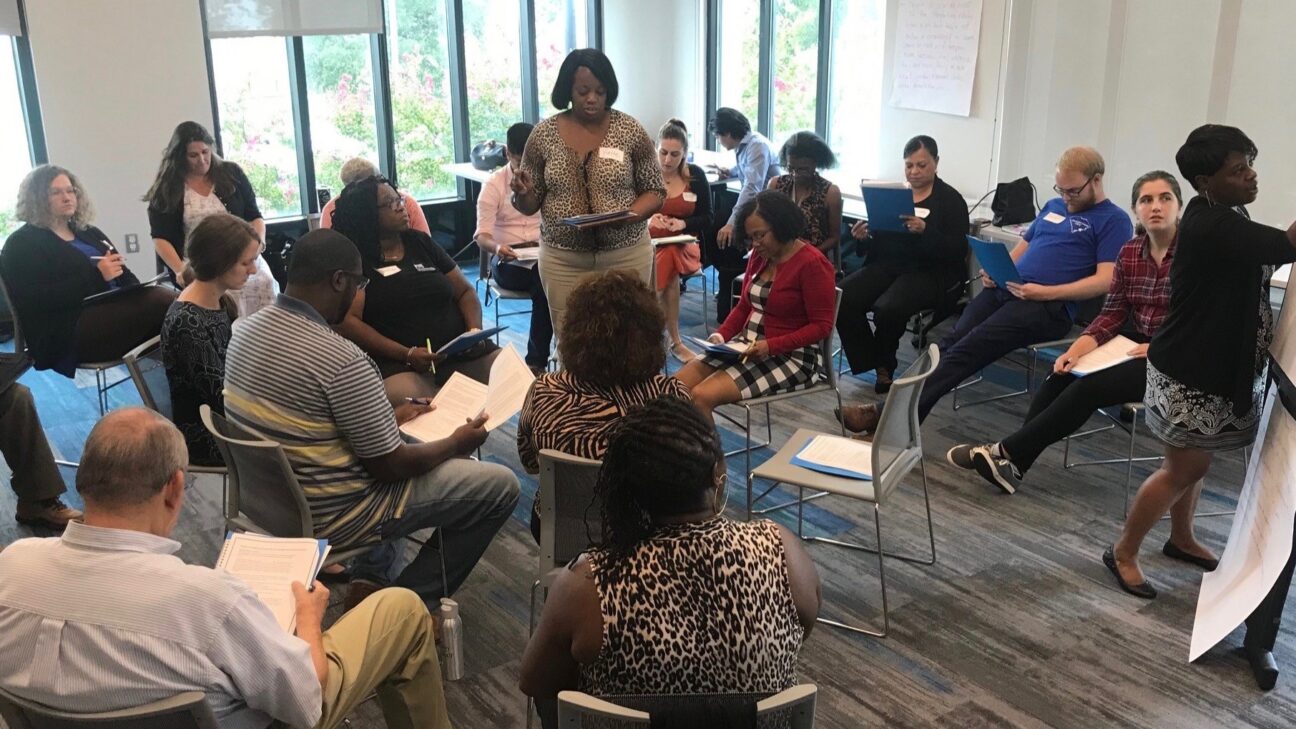

In the Same Room

Members say they avoided a disconnect between community and grassroots members and policy experts by keeping everyone at the table. Community groups often spend years advocating for change but are left out when policies are written. To avoid that, the Coalition insisted that those representing grassroots and community groups meet together with policy experts.

“I often joke that we don’t let the lawyers meet without the community groups. But over time, that’s also true that we don’t want community groups meeting without the lawyers and policy experts because our strategy in the community should be informed by what’s actually possible in the legislature,” McLoughlin said.

Watkins, who led SOUL, agrees that the Network’s success was due to its members respecting each other’s expertise without interfering in their work.

“The policy people weren’t in vulnerable communities trying to hold conversations with residents, and they shouldn’t be. Groups like SOUL were on the ground listening to people’s real stories. We’re a Black-led, Black-centered organization because that’s where we come from,” she said. “Having a diverse array of individuals who deeply respected each other was unique. It wasn’t folks convening us; it was the other way around.”

Combating Misinformation

Illinois faced a well-funded, sometimes racist, misinformation campaign after the Pretrial Fairness Act passed and before it went into effect. A mailer, styled as a newspaper with images of mostly Black men, was sent to Illinoisans statewide. Social media posts called the new law “The Purge,” a reference to the dystopian horror films in which all crime, including murder, is legal for 12 hours.

McLoughlin says they studied similar misinformation campaigns in New York, where media often reported claims about reform and crime rates without evidence. The Network developed rapid responses to misinformation and demanded corrections or the opportunity to comment. (The Center for Effective Public Policy, which manages the APPR project, collaborated with the Network and other partners on these communications efforts.) Members also organized periodic media briefings in Springfield, the state capital, and Chicago, a major U.S. media market. The steady engagement with the media eventually led to more fact-based, nuanced, and contextualized reporting on the impact of the Pretrial Fairness Act. [1]

Watkins recalled how community and state legislators came together after a paid campaign to spread fear hit Illinois. SOUL organized an event to counter the misinformation. “It was amazing. Hundreds of community folks telling our stories alongside legislators. Seeing legislators alongside formerly incarcerated people saying, ‘We are doing this together, and the community is standing behind us.’ That is the most important moment that I will probably ever witness in my life.”

Cook County Public Defender Mitchell says the responsibility to explain how the criminal legal system works should not fall solely on community groups.

“We can run into real trouble as a society if people aren’t educated about the law, if people don’t know about the rules that govern their everyday [lives]. We put ourselves at a real disadvantage as a democracy if we [attorneys and judicial officers] don’t take up the responsibility of educating people about how this system works,” Mitchell said.

“Long-Term Struggle”

Since the Pretrial Fairness Act was implemented, judges, prosecutors, public defenders, and law enforcement have acknowledged the benefits of a system in which money plays no role. The Network remains actively engaged in working to adequately fund public defense, educate the public and media as pretrial data becomes available, and monitor that the law is implemented with fidelity.

Watkins remembers a Chicago organizer talking about long-term struggle. After the Pretrial Fairness Act passed, she said the phrase had a deeper meaning.

“I am so proud of this coalition for not walking away,” Watkins said. “The legislation is only as good as how you continue to shape it while it’s implemented, and we have to constantly fight for more. We no longer have money bond. How else do we actually keep people out of cages and in communities and homes and jobs and families? That is what we are ultimately pushing for.”

2016

- The Coalition to End Money Bond is formed, and members agree to the Principles of Pretrial Reform in Illinois. Its work is focused on pretrial justice in Cook County (Chicago), Illinois.

- A class action lawsuit sues Cook County for unconstitutional use of money bond.

2017

- In response to the lawsuit and Coalition advocacy, Cook County Circuit Court issues General Order 18.8a, creating a process aligned with state law that indicated monetary bonds should only be set in amounts that people could afford.

- The Coalition urges the Illinois Supreme Court to issue a similar order statewide. The court forms a task force to study pretrial practices in the state.

2018

- The Coalition gathers signatures and successfully advocates for the Supreme Court’s Commission on Pretrial Practices to hold public hearings.

2019

- The Coalition to End Money Bond launches the Illinois Network for Pretrial Justice to advocate statewide pretrial improvement. Members of the Coalition are also part of the Network, along with groups from outside Cook County.

- During the task force’s public hearings in Springfield, Champaign-Urbana, Chicago, and Freeport, more than 100 people testify in support of money bond reform.

- The Coalition issues the report, Pursuing Pretrial Freedom: The Urgent Need for Bond Reform in Illinois.

2020

- Governor JB Pritzker announces that his administration supports ending the use of money bond. In response, the Coalition publishes its Vision for a Just Pretrial System: How to End Money Bond and Increase Pretrial Freedom.

- Illinois Supreme Court Commission on Pretrial Practices issues its final report. The report does not recommend eliminating financial conditions of release because task force members did not reach a consensus.

- The Illinois Supreme Court creates the Pretrial Implementation Task Force, whose membership includes representatives from the Network, to implement the report’s recommendations.

- The Network issues a report, Evaluation of the Illinois Supreme Court Commission’s Final Report and Recommendations.

- The police killings of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd spark widespread protests and national attention on police violence and racism, mobilizing more people and support for reform in Illinois.

2021

- The Illinois legislature passes, and the governor signs, the Pretrial Fairness Act as part of a broader set of criminal justice improvements known as the SAFE-T Act.

- The Network publishes From Policy to Progress: A Roadmap for the Successful Implementation of the Pretrial Fairness Act.

2022

- During the 2022 state legislative session, the Coalition and Network released $tate of Injustice, documenting community court-watching efforts and identifying the negative impacts of the current pretrial system and its dependence on money bond.

- Paid and earned media campaigns circulate fear and misinformation. In response, the Network releases Obscuring the Truth: How Misinformation is Skewing the Conversation about Pretrial Justice Reforms in Illinois, a resource for reporters and communities.

- A legislative trailer bill passes that upholds the spirit of the Pretrial Fairness Act.

- Litigation delays implementation of the Pretrial Fairness Act.

2023

- The Illinois Supreme Court affirms the law’s constitutionality, and the Pretrial Fairness Act goes into effect in September 2023.

2024

- The Coalition and Network work to support the successful implementation of the Pretrial Fairness Act through media education, including media briefings.

- The Network and legislative partners successfully advocate for state funding of voluntary, community-based services for people awaiting trial in areas without adequate access.

- The Network advocates for legislation to create a state office of public defense and more adequate funding for public defense statewide.