Colleen Clark-Bernhardt knows that if her county is going to improve its pretrial system in lasting, effective ways, community members must have a meaningful role in the process. The Dane County (WI) Criminal Justice Council (CJC) is engaging people, including those who have been involved in the criminal legal system, “to shorten the gap between government and community,” says Clark-Bernhardt, the CJC’s coordinator.

Dane County implemented the Public Safety Assessment (PSA) in 2016, and the CJC is involved in ongoing efforts to improve the pretrial process. The CJC led trainings on pretrial best practices; in 2019 that included leaders from the Madison Police Department, the Dane County District Attorney’s Office, and the Dane County Clerk of Courts (which is responsible for pretrial assessment and community supervision) participating in a series of listening sessions with local residents at two community centers and a church.

As Clark-Bernhardt describes it, “Leaders had an opportunity to break bread, share their perspective, and listen to members of the community.”

Some community participants had personal experience with the criminal legal system; others were advocates or simply interested residents. At each session, the institutional stakeholders were at different tables and would sit with groups of community members. Each table also had a notetaker and a facilitator. The groups of participants would move from table to table until they had talked with all three represented organizations.

“We’re so glad you came”

“They were interested, motivated, and loved the fact that stakeholders were coming to community,” Clark-Bernhardt says. “The downside involves specifics related to an active case. It can be really hard for a prosecutor or a cop to get questions about active cases, which they can’t comment on. Another downside is that people ask, ‘Why don’t you guys come out here more often?’”

“And then on the upside, they say, ‘We’re so glad you came. We really appreciate that you’re feeding us and respectful and valuing our time as community people.’” (Although the county typically can’t spend money on food without passing a resolution, grant money paid for the meal provided to participants.)

The listening sessions helped Dane County identify the community’s concerns and misperceptions about the front end of the criminal legal system. As Clark-Bernhardt explains, “It helped us identify the questions the community has and then ask, What data can we collect that will be useful to pretrial and other criminal justice practitioners? The hope is that advocacy groups can also use our data to inform how they interact with community members.”

Authentic Partnership

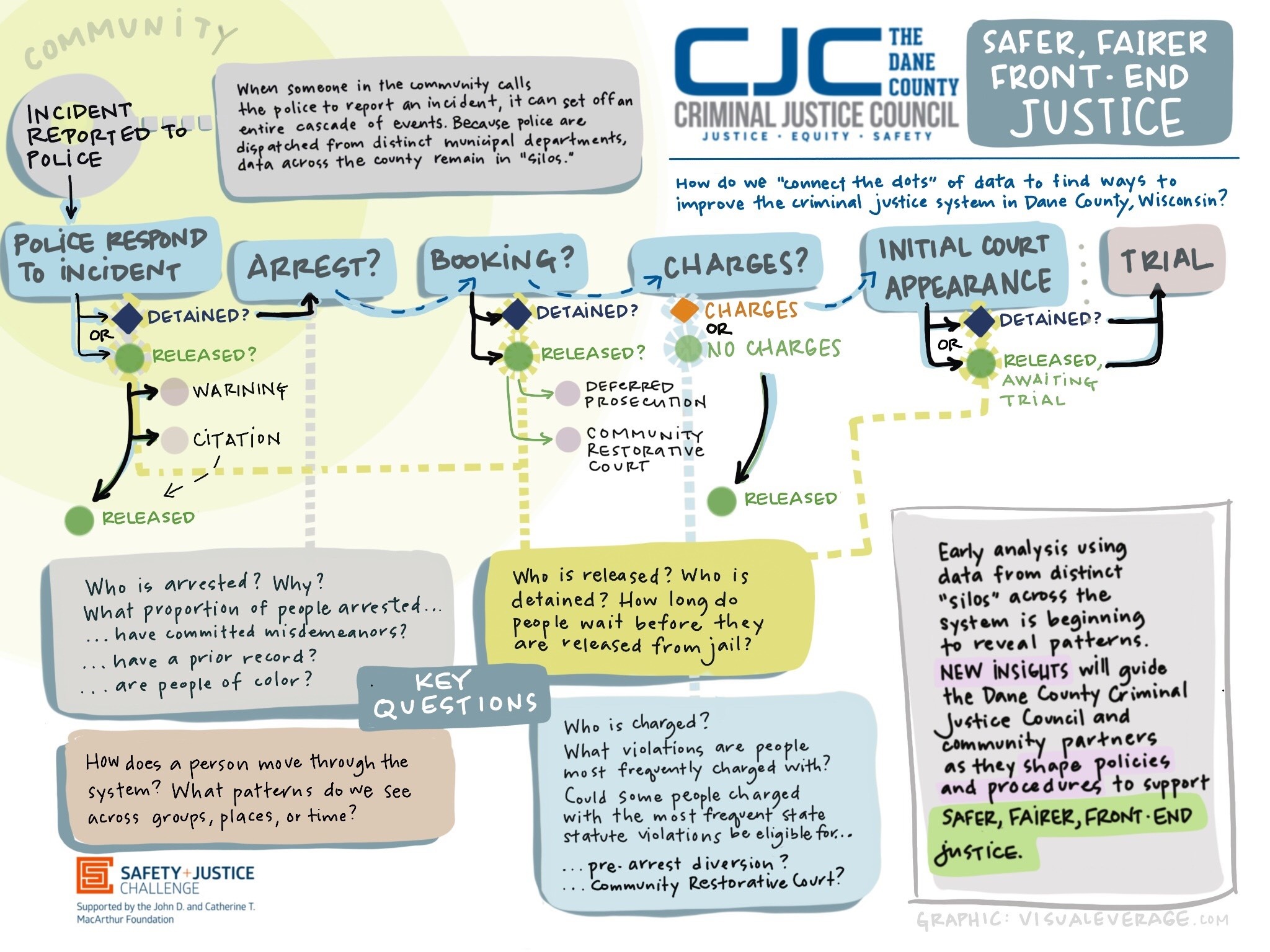

As a follow-up to the listening sessions, the CJC developed a two-page overview of the county’s pretrial system for public education. The CJC also created a one-page graphic flowchart depicting the possible steps and outcomes from the time an incident is reported to police through the resolution of a case. The sessions directly contributed to the graphic flowchart, which tried to synthesize the questions raised by community participants.

Clark-Bernhardt says the CJC has recently hired seven Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) community leaders. The seven groups they work with are working on a needs assessment for a potential community justice center.

“Usually, government has something fully developed and says, ‘What do you think, BIPOC community?’ That means they’ve had no ability to shape; they’re either rubber-stamping or making tweaks. We’re much more centered on community, reaching past outreach and past services into true authentic partnership.”

“I often say that a trifecta is required to move system change: community voice, data, and stakeholder collaboration. If I don’t have all three of those, it’s really hard to get from an idea to implementation,” Clark-Bernhardt says.

Clark-Bernhardt hopes the CJC—and more broadly, the county and other funders—can budget for the community justice center being considered: “It’s yet to be shaped, but racial equity, diversion, and wraparound services will be major tenets. I can picture future pretrial services being in a community justice center.” She also suggests that peer mentoring could be included as part of the pretrial supervision services offered in Dane County.

Clark-Bernhardt thinks of pretrial as “pre-entry.” “Pretrial is the other side of the coin—of reentry—and, nationally, I don’t think people treat it the same way. The community organizations that do the same kind of case management for reentry—on jobs, housing, and other supports—could also be partners on the front end. We’re concerned about the racial inequity in our system, so how do we keep people from coming through that front door?”

Through greater community engagement, enlisting those with lived experience, and accurate data, people in Dane County hope to do just that.

About the Author

Jules Verdone is a writer and editor whose clients have included the Center for Effective Public Policy, the Center for Policing Equity, Common Justice, the Criminal Justice Policy Program at Harvard Law School; the CUNY Institute for State and Local Governance; Fair and Just Prosecution, the Katal Center for Equity, Health, and Justice, the National Bail Out collective and the Vera Institute of Justice.