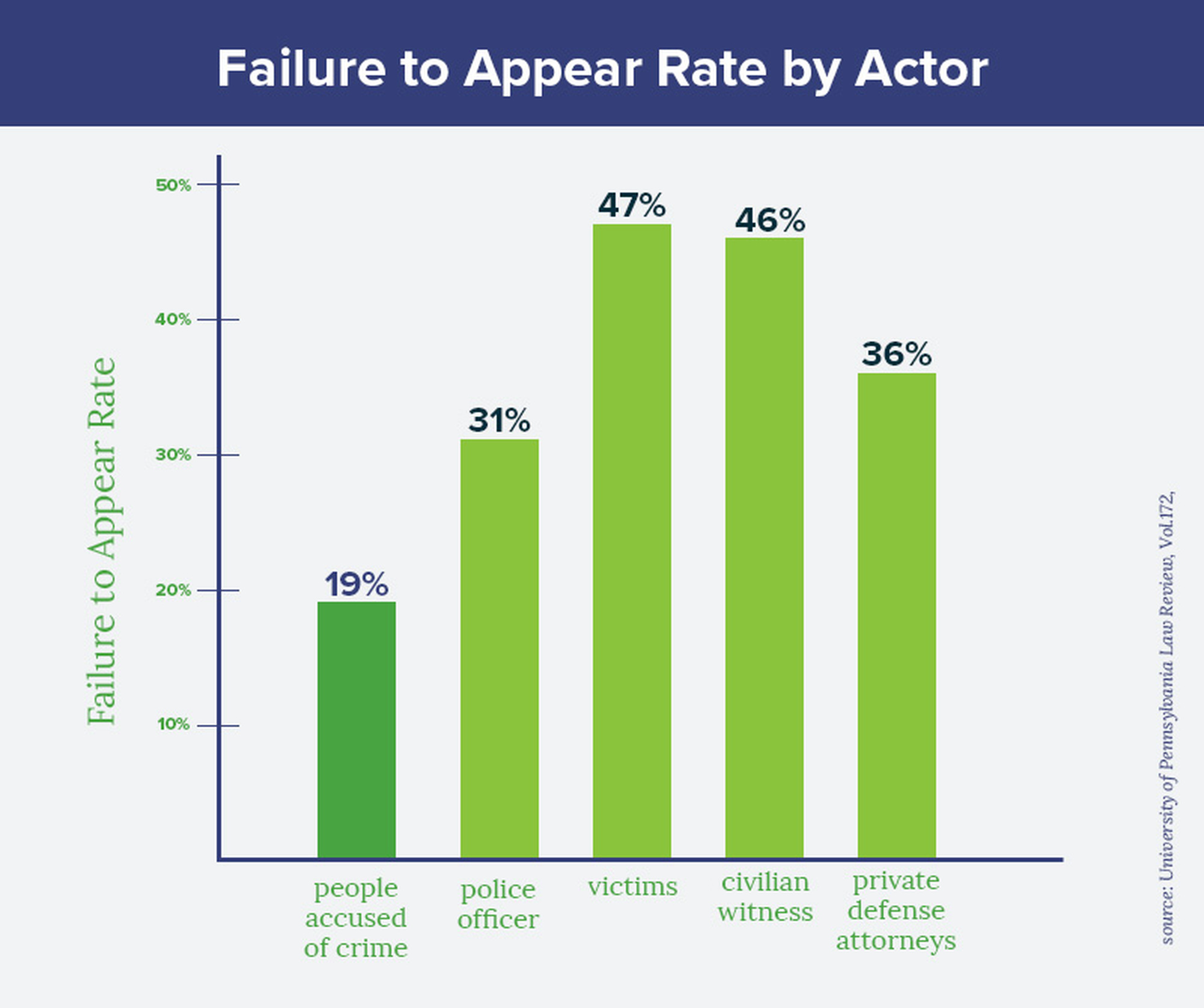

The criminal legal system focuses intently on whether people accused of a crime show up for court. The consequences of missed court appearances can be severe, including a warrant for arrest and pretrial detention. However, a new study found that criminal legal system stakeholders—police, attorneys, victims, and witnesses—failed to appear [a] more often (53 percent) than accused people (19 percent). This research, which used 10 years of data from Philadelphia, has broad implications for how we define, measure, and respond to failures to appear (FTA) by all people.

APPR spoke with two coauthors of Systemic Failure to Appear in Court. Dr. Megan Stevenson is a professor of law and economics at the University of Virginia School of Law, and Lindsay Graef is a doctoral student in the Department of Criminology at the University of Pennsylvania. The interview was edited and condensed.

APPR: Failures to appear by actors other than accused people haven’t previously been examined. What led you to conduct this study?

Dr. Megan Stevenson: I was working on a project called Does Cash Bail Deter Misconduct? with Dr. Aurélie Ouss, another co-author on this study, developing a measure for failure to appear using information from the court clerk’s notes. We noticed a lot of failure to appear by actors like police and victims and others, and we thought we should look into it further. Lindsay had a similar experience.

Ms. Lindsay Graef: I noticed the same thing while observing court. I discussed it with Dr. Ouss, Dr. Stevenson, and our colleague, Dr. Sandra Mason, and it came together from there.

APPR: Your data and conclusions are striking. Are criminal legal system actors surprised at your findings, especially in the courts? Were you surprised?

Ms. Graef: We’ve heard that many people are surprised by these numbers. We presented our findings to the district attorney’s office, and they were not surprised, but they’re grateful to have data on this phenomenon they see every day.

A big issue is that there’s currently no way to track these FTAs—the system doesn’t have this information. So now different agencies are looking at ways to track and measure it so they can respond.

APPR: You found that police officers failed to appear at least once in 31 percent of these cases. Can you say more about that?

Ms. Graef: We conducted interviews in addition to analyzing the data, and those suggested that some police FTA is willful, but we think a lot of it is due to logistical barriers and dysfunction. For example, police FTA rates are higher for DUI [b] and drug cases, many of which happen at night. Those night-shift officers need to sleep and attend to personal business during the day, which is when court is held. Also, officers told us that, due to staffing shortages, they are pulled between a lot of competing priorities.

APPR: Are there consequences for officers who miss court?

Ms. Graef: There isn’t currently a way to track officer FTAs, so there’s no way to enforce court attendance. Police policy directives state that court appearance should take precedence over anything else, but that doesn’t happen in practice. The police are aware of the problem, and hopefully, with better data, they can figure out some solutions.

APPR: What did your interviews uncover about police FTA that is more willful?

Dr. Stevenson: We found several reasons officers might purposefully fail to appear in court. Especially for lower-level cases, officers may make a calculation—consciously or subconsciously—that the person’s arrest and a few days in detention are punishment enough.

Ms. Graef: Police can exert a lot of power over the prosecution process. Their failure to appear is basically dispositive [c] for these cases.

Dr. Stevenson: Right. And our data showed that officers are more likely to appear in serious cases, which fits into that notion.

Another reason is if officers made an error, a Fourth Amendment violation, or were too rough, they may be reluctant to have that behavior exposed in court. That’s disturbing because these possible abuses never come to light if the case is dismissed because the officer fails to appear.

To me, police FTA is especially problematic. It’s part of an officer’s job to show up in court. They get paid for it. Their own rule book says they are supposed to prioritize appearance. Having representatives of the legal system fail to appear at such high rates is unacceptable. I hope that the police will take some accountability for this and do what they need to do to fix the problem.

APPR: You also looked at FTAs by civilian witnesses. What does it mean when witnesses fail to appear?

Dr. Stevenson: In our study, we found witnesses failed to appear 47 percent of the time. Witnesses are legally required to attend court hearings. But getting to court can be a real logistical burden. Witnesses face the same hurdles as accused people when getting to court, and usually, each case has multiple hearings. It’s a hassle, and many people don’t want to bother with it—for many reasons. Witness intimidation is another factor. Legally, we can detain witnesses to make sure they appear in court. But that almost never happens.

“To me, police FTA is especially problematic… Having representatives of the legal system fail to appear at such high rates is unacceptable.”

If a witness is central to a case, you can’t do much if they don’t show up. You can file a continuance or try to track them down if you have time, but ultimately, if the person’s not coming to court, you drop the case. We found that cases were twice as likely to be dropped if a witness failed to appear.

APPR: The FTA rates among victims were exceptionally high. How do you interpret that?

Dr. Stevenson: Victim FTAs are stratospheric, particularly in domestic violence cases where around 70 percent of witnesses fail to appear.

We think the current criminal legal system, with all its hassle and dysfunction, is just not providing solutions to people’s problems. People often invoke victims by saying, “We’ve got to be tough on crime for the victims,” but if you look at what victims are actually doing, frequently, they’re just opting out of the system entirely. And I think that’s worth taking a pause and thinking seriously about.

APPR: This paper is a wealth of interesting data and insights. Is there a big takeaway?

Ms. Graef: One is rethinking what we’re measuring when we measure FTA. We assume we’re measuring the risk an accused person poses. But actually, a huge part of what we see as risk is really the system’s own dysfunction and logistical barriers. Looking at FTAs across all parties, we start to see that the drivers are more related to planning and coordination.

Dr. Stevenson: To me, it’s that the risk of FTA is just a ruse for pretrial detention. The impacts of FTAs—the hassle, dysfunction, wasted time, and wasted resources—are basically the same no matter who fails to appear. From that perspective, witness FTA and defendant FTA are exactly the same. So it makes you think: if jail is so harmful that we virtually never detain witnesses, why are we so comfortable detaining defendants at such high rates? If we took the presumption of innocence seriously, we would treat accused people on the same moral standing as these other actors.

But we also expect a significant proportion of these FTAs to be amenable to system-wide solutions. Things like easier scheduling, improving court websites, better timing of hearings to reduce waiting time, and consistent reminders and text messages. You can do these things for everyone.

Study Findings

Study findings include:

- FTA is a systemic phenomenon, not limited to people accused of crime.

- People accused of crimes fail to appear (FTA) less frequently than other parties (19 percent vs 53 percent).

- Other parties’ FTAs significantly impact case outcomes, increasing the likelihood of dismissal.

- FTA rates of victims (47 percent overall, 69 percent for domestic violence victims) suggest that they are frequently opting out of the justice process.

- There is a stark asymmetry between responses to FTA for accused people and system actors.

- Prosecutors and public defenders rarely miss court because they are nearby and can find other attorneys to attend hearings if they cannot.